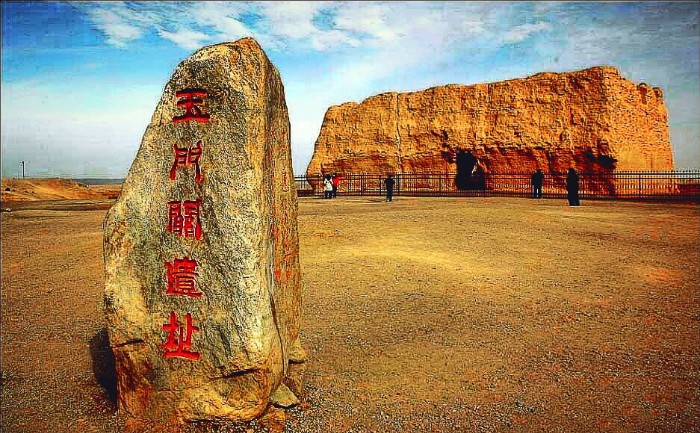

Standing alone in the middle of the desert, yumen pass, also known as xiao fang bao, has lost its luster as an invincible military fortress. It may be hard to believe that this dilapidated site of rammed earth was once a fierce battlefield and a thriving trading gateway, with traders and camels coming and going.

It was an important pass at xiguan in the han dynasty (206bc-220ad), at the western end of the hexi corridor, the gateway from central China to the west.

As a vast and complete ancient defense system, the Great Wall, broadly defined as a strip centered on a passageway, is 25 miles (40 kilometers) long and 550 yards (503 meters) wide, including two castles, 20 beacon towers and 17 wall sites.

Yutian hetian jade is located in the world’s oldest international trade route — the northern section of the silk road. In ancient times, the hetian jade in yutian (today’s hetian county, xinjiang) was transported to the central plains through the pass, hence the name yumen pass.

The pass was made of rammed earth and had two gates, the west gate and the north gate, the latter being the main entrance. There were several offices and a staircase at the southeast corner leading to the attic. However, due to thousands of years of disrepair, these sites cannot be found at present. The remaining castles cover 757 square yards (633 square metres), are 26.7 yards (24.4 metres) long, 28.9 yards (26.4 metres) wide and 30 feet (9 metres) high.

On June 22, 2014, yumen pass became a world heritage site. In the early han dynasty, xiongnu constantly invaded the western frontier of China. Instead of fighting back, the weak rulers of the country preferred to marry the maids of honor to the chief of the xiongnu to obtain temporary peace. When emperor wudi came to power, he immediately abolished this cowardly policy. He launched a massive and violent counterattack, driving the xiongnu army out of the territory. In order to strengthen the stability of the western frontier, two passes of yumen pass and yangguan pass were set up along the border. From then on, these two passages, like two royal soldiers, gloriously defended the west gate of their country.

Located on the northern part of the silk road, yumen pass was also a stop for merchants and envoys. It witnessed the prosperity of commercial trade along the old trade routes. Silk, porcelain and tea flowed to the west. At the same time, spices, fruits, music, religious beliefs and other western specialties were introduced into the central plains. It is said that grapes, pomegranates and walnuts, which now grow in central China, are native to the western region.

Two thousand years later, the camel bells had died away. The cries of the sellers in the market completely disappeared. There is only a single castle left to remind you of its glorious past.